The distinction between myth and what we occidentals

describe as 'reality' does not exist in India where even the passage of

time is illusory. A religious festival merges myth and sacred time with

the ordinary temporal flow.

Arunachala

was worshipped long before the Vedic culture penetrated the southern

peninsular millennia ago. In the south Lord Siva was the notion of most

awesome significance and Arunachala became the embodiment of Lord Siva.

[Kailash Mountain of Tibet is his abode where he meditates, but

Arunachala Mountain is The Lord Himself]. Lord Siva showed himself as

the eternal principal in the form of an endless column of Light, the

light of consciousness through which realization is possible. Invisible

it is to mortal eyes, it is called the Mahamangalam, the Great

Auspiciousness. Arunachala Mountain is an icon or indicator of this

presence of power.

It was

in comparatively recent history that the Vedic Divine personalities such

as Lord Siva evolved on the subcontinent; they up-staged the primeval

pantheon of elemental divinities worshipped since time before mind:

Fire, Water, Space, Air and Earth. Sacred places associated with these

most ancient divinities all lie in the South; Arunachala is The Fire

Place.

|

|

Agni is

the ancient deity commonly known as the god of fire. This element has

three forms and the form significant for Arunachala is the most subtle

form of light. Arunachala is an invisible column of light signifying

consciousness. In case you do not know I should mention that Human

consciousness veils our original identity and paradoxically it is the

means by which we can recognize our original identity - or true nature,

prior to consciousness. This realization confers freedom from the

bondage of embodiment. The light of the Deepam flame on Arunachala is

lit according to the lunar calendar exactly as the moon rises into

Karthigai month so it is called Karthigai Deepam; it reminds us of our

inevitable enlightenment.

The original myth

associated with Arunachala Deepam is this: Aeons ago the gods Brahma

and Vishnu challenged one another; each claimed to be able to reach the

end of the universe. Brahma (the Creator) headed up into the sky in the

form of a swan, and Vishnu (the Preserver) headed down into the earth as

a boar. Neither managed anything much, except attempts at trickery -

both cunningly claimed to have found the end. The Destroyer of Ignorance

- Lord Siva - pronounced the justice of this situation: that no

embodied being has precedence over any other; that only what is prior to

consciousness is real. What is real is quality-less. It is eternal,

univocal throughout all dimensions of all worlds.

Deepam Festival lasts fourteen days. The Big Temple displays its

treasures every night of the first nine days in processions around the

circuit of streets in town. Millions of pilgrims come, perhaps two

million sometimes, perhaps more; they camp out in the temple complex and

fill every available hut, home, shop, guesthouse, ashram, room, corner,

balcony, corridor, niche, stone bench, and nook under trees and rocks.

They all walk around the hill; some many times because it is exceedingly

auspicious to do so. Lord Siva may very likely grant a pilgrim's

wishes.

Many

years ago when my daughter was small, the old infirm lady who lived with

us - an elderly Brahmana woman of ninety-nine-odd years - used to

bundle her pots and pans, condiments, clean white saris - she'd bundle

them all up in a cloth and scoot off by rickshaw into town for Deepam

every year. She had an age-old arrangement with a family in the main

street, she used to camp on their verandah for the ten days, staying

awake at night to worship the gods as they came past. The divinities

would no doubt reward her for all her trouble.

Although

we are tempted to conjecture that the motivation to partake of this

exceeding auspiciousness arises from other-worldly concerns lured by the

possibility of relinquishment from the cycle of birth and death, this

is not entirely true. For the Hindu it is considered monumentally

difficult for an individual to achieve the freedom from attachment to

this world that is essential for absolute freedom. It is love of this

world that fires the hearts of the devotees; the possible fulfillment of

desires sustains arduous pilgrimages. The number of pilgrims walking

around Arunachala has increased so much during the past ten years that

we now have a mini-Deepam every single month. A famous film star's

pronouncement that Arunachala grants wishes at full moon as well as at

Deepam is what started it all off. Since then, the entire town has to be

frozen of incoming traffic for the duration of the moon's radiant

fullness and thousands of extra buses are scheduled. The ostensibly

other-worldly Deepam festival is actually a tremendous affirmation of

confidence in life on Earth.

Hawkers

come with their wares: food in particular and pictures of gods, film

stars and politicians. Hawkers bring spiritual books, protective

talismans, plastic toys and bunches of grapes, things to hang on your

rear vision mirror and stand on your TV, wind chimes, socks, belts,

warmers for heads, underpants, bangles, molded plastic divinities, fruit

trees, pillows and blankets, jewels, hair clips, watches, fruit trees

and motor bikes - to name a few conspicuous items. The religious

festival becomes a vast marketplace. The Holy Hill is garlanded with

opportunities.

Beggars

come by the busload with their leprous legs and stumpy arms and their

begging bowls; some have little vehicles. Sadhus come in orange - the

mendicant's uniform. Businessmen also come. Families come with plastic

carry bags of clean clothes and blankets. With their shaven scalps

smeared with turmeric paste; they wash their saris, dhotis and shirts in

the tanks beside the hill-round road route and walk with one wet sari

end tied modestly about their body - the other held by a family member

up ahead, the cloth streaming out to dry in the breeze. Skinny people

with big feet and wide eyes: these are the true-blue pilgrims who camp

on the flagstones of temples and mandapams. Modern middle class families

stay in expensive hotels. Groups come with musical accessories and

flower garlands, voices joining footsteps. The Hill becomes garlanded in

humans, encouraged by the voices of the hawkers and bucket loudspeakers

blaring from the frequent stands selling tapes of devotional music.

A recent

upsurge in progress has resulted in the construction of several sheds

along the way, in which pilgrims can rest and watch TV. A special cable

was laid to provide video images of the festival happenings including

much film of pilgrims walking around the Holy Hill so that resting

pilgrims can even see themselves perhaps, by courtesy of our recent

technological achievements.

It is

widely believed that the provision of Free Food at Deepam is rewarded by

the Lord more than any other provision of Free Food! Down at little

shrine area in the only remaining virgin forest adjacent to my house, on

one side of the road every year we have The Big Temple servants feeding

ten thousand persons a day, and on the other side another group feeding

another ten thousand. Crowd Control Barriers sprout and the vast

distribution of free food manifests itself all along the Hill Round

Route.

We

wandered down to the little shrine area around midday on the seventh day

of last year's festival - the day of The Lighting. The Free Food queue

in the crowd control barrier on one side of the road extended back for

more than a kilometre, forming a static block against the jabbering

stream of thousands not interested in free food just then. The field

behind where the forest watchman lives was full of onionskins, vegetable

peelings, big pots being filled with food and big pots on fires. Full

steaming-hot big pots were carried on palanquins by strong men across to

the awning on the roadside where more big pots of hot food were lined

up and many men were dishing spicy rice onto leaf plates for the long

barricaded queue of hungry Tamilians extending out of sight.

We ate

our free food on a bench segregated from the crowd by thorns, watching a

big fight between temple bouncers and persons trying to eat their food

too near to the distribution spot, thereby creating untold congestion in

a greatly congested situation. There was no alternative since there was

nowhere to go to eat, because the sea of human beings takes up every

available space. Discarded leaf plates smeared with spicy rice covered

the road and particularly the shoulders of the road, where one had to

wade through a great mess in order to move. Huge religious festivals

have an agonizingly sordid side. But the ecstasy is something else.

Three

days before the lighting of the Light, it is Big Car Day. There are

several Big Cars, huge wooden carts carved with fabulous mythological

figures telling all the stories, with the biggest wheels in the world;

the biggest car dwarfs all the buildings in town except the giant temple

towers. It is called The Big Car.

Our

temple elephant leads the procession. Several elephants come for Deepam,

most of them beggars; they walk from wherever they come from. On this

day parents or family members also carry their babies around the

procession route. They string a sari on a sugar-cane pole which they

support on their shoulders making a hammock for the child. The babies

carried are ones whose parents asked Arunachala to bless them with so

they are carried in thanksgiving.

The

splendid bronze figures of Annamalai and Unnamalai - male and female

personifications of Arunachala, are heavily garlanded and bejeweled,

seated up on The Biggest Car; the towering edifice is covered with long

strips of embroidered cloth and gigantic flower garlands. There are

several big cars pulled before and after The Big Car; there's a

women-only one carrying Abhithakuchalambal, and there's also a kids'

car, which trails flamboyantly at the end. It's all stupendously

awesome.

Years

ago we used to walk in to watch the Big Car come up the incline of one

main street around midday; for years and years and years, we'd all have

lunch in ashram and then everyone would make their way around to the

east face of the hill to meet the gods coming up Thiruvoodal street. But

now there are so many pilgrims that the schedule has extended

interminably. Inauspicious times of the day intervene so the proceedings

stop until the bad hour has passed, and there's also the time when

suddenly everyone goes home for lunch.

That

year it was evening before the Big Car reached that street. My

daughter's two children - Hari and Ani - were very young so we secured a

protected view from the balcony of a cloth shop half way down the

incline, long before the towering, tottering, embroidered, garlanded Big

Car - with it's flouncing umbrella on the very top, appeared above the

roofs of the shops and maneuvered itself into position for the strenuous

haul up towards Arunachala. Upon the up-roaring signal of its

visibility from the crowd, Hari dropped his pile of coat-hangers and

rushed to be held up over the balcony. His eyes popped, his ears

flapped. Even though we'd seen it before, nothing can prepare us for the

majesty of its annual sight. Below us the street was a sea of heads;

all balconies and rooftops up and down the street full of faces and now

that the Big Car appeared, bodies behind us pressed forward, pushing us

onto the balcony rails festooned with dubious electrical fairy lights.

It's quite exciting.

Since the divinities are coming, dedicated persons don't wear

shoes. This year we noticed one Policewoman wearing socks to protect her

dainty feet from the yucky street. About five thousand pilgrims pull

the cart around the temple circuit-route, ladies on one side and gents

on the other. When the car stops, big chocks of heavy wood are wedged

underneath the enormous wheels while the pullers take a rest and

offerings are made to their majesties the gods. When ready to start

again, young men with enthusiasm climb up onto the chocks with poles to

steady themselves, and on signal they jump up and down on the slanted

chocks until their force pushes the wheels forward, giving momentum for

the pullers to haul the cart further up the street.

Looking

down into the crowd below as the cart passed beneath us, we were treated

to a seething mass of human energy - drums beating in time to muscles,

bystanders shouting encouragement, enormous wheels slowly turning, the

carving on the cart creaking, embroidery panels blowing in the wind,

garlands wavering about, lucky little boys sitting up high lowering

cloth carry bags on strings for people to send up coconuts and flowers,

the Brahmin priests looking down impassively.

It's the

Brahmins particularly - the extravagant courtly costumes, the imperious

faces staring down - that convey the true sense of the gods as

majesties: as the most important personages in our world, out on a tour

of the town, to be saluted by their adoring subjects. And a very large

number of their adoring subjects are sweating, straining at the edge in

the effort required to pull them. The Big Car teeters its way uphill

until the momentum runs out. The chocks are wedged in again. Everyone

breathes. It will take about ten hours to circumnavigate the temple."

Many are

the occasions of inspiration throughout this festival but the

outstanding event is the lighting of the Light.

This

year my dog and I walked with our friend around to the temple dedicated

to the feminine aspect Unnamalai lying on the west of Arunachala where

the Shakthi - the female power point of the hill - peeks up from behind

the main protuberance. This peeking point is a perfect little inverted

vulva; it even has a little clitoris sticking up, perhaps it's a bush.

Unnamalai Temple has a gorgeous stone-pillared mandapam, or hall, now

newly painted and overflowing with pilgrims. And across the road, on the

hillside, spreads a newly cleared Restawhile Park with a modern iron

umbrella above cement benches. The Restawhile Park is a perfect viewing

place for the lighting of the Light.

Underfoot

is conspicuously sordid by this time in the Festival so our walk to the

temple had meandered around piles of garbage. We passed a balloon man

with his happy crowd of prospective little buyers and the nice clean

boys selling 'Healthy Milk Drinks' next to the stacked plastic bottles

of unhealthy pop shop. Outside Unnamalai a stall selling cheap

audiotapes was blotting out existential consciousness entirely yet the

ceremonies in the temple were going strong - assisted by other

loudspeakers, and the pilgrims were slapping their cheeks and bowing

down in obeisance the way they do. None of the local dogs were visible;

we noticed this, my dog and I.

We sat

for awhile under a tree near to the shrine next to dear sadhu Ramana in

yellow, who spends all his livelong days sweeping the hill round

roadway; he had merged with the tree and didn't look too enthusiastic.

Across from me on the hillside sat the irascible sadhu, for once amused,

and behind him rose a crassly painted modern iron umbrella sheltering

the concrete benches which provide sadhus with such an excellent place

to dry their cloths, two sadhus were folding dry orange dhotis

diligently and behind them the cheeky little Shakthi and the great peak

loomed resplendent in the distance.

As dusk

approached we sat down near to the sadhu to wait for the flame to

appear. We could smell human shit there; we watched pilgrims daintily

picking their barefoot way across the weeds hoping to avoid any mess

before sitting down nicely cross-legged to stare up at the mountaintop.

Gradually the Restawhile Park's uncontaminated spaces filled with quiet

orderly pilgrims. We had to wait about an hour, and we foreigners

couldn't help but notice that nobody was eating, smoking, talking or

drinking. Some had lit incense. For thirty kilometers radius surrounding

Arunachala at this time several million people were waiting

suspenseful, staring up to the top of the hill, as they always do.

Up on

the narrow rocky top of the mountain stands a gigantic copper lamp

laboriously carried up that morning by a team of old blokes in

loincloths who are traditionally honored with this task. The east face

is swarming with humans on their way up with clay pots of ghee to

replenish this lamp; a colorful pilgrim snake weaves the traditional

path and more adventurous persons scramble up in other directions. The

almost top plateau becomes a mini-market, even bangles and balloons can

be bought up there, and many will spend the night beside their wares.

The very top is standing-room-only of course - for men only; bare feet

negotiate the brittle remains of broken clay pots softened by the sticky

ghee surface of centuries. Everyone takes up flowers and incense to

enhance the honour of presence.

A

special ceremony in the Big Temple in town early this morning

accompanied a flame-seed from the inner sanctum out into the enormous

flagstone courtyard where it first lights another flame-seed set waiting

beside another huge copper lamp, before traveling carefully up the path

on the east face to the top. There it will be sheltered by the priests

in breathless expectation of the rise of the auspicious full moon. Any

parts of this ritual which are now left out or compromised by human

weakness are just the effects of the degeneration of the times.

The

moment our Celestial Orb appears on the eastern horizon the giant lamp

on the very top will be lit and the moment the little flame on top

appears, the priests in the Big Temple will light the big lamp in the

vast courtyard so packed with humans now chanting "Om Namo Sivaya" that

if the festival is pelting rain - as it sometimes is - it is surprising

how the heat of so many bodies keeps them somewhat warm and dry. The

temple elephant also waits with the crowd; this is part of her job. She

loves festivals.

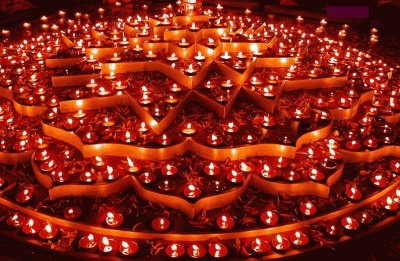

The appearance of the light on the top will also signal orchestration of

thousands and thousands of small Deepam lamps set waiting outside huts

and households as far as eye can see. This is the Festival of Light,

remember? Many household lamps are mountains of sweet rice-flour, with

ghee to carry the flame, as Pati used to make for us during those years

between the infirmity preventing her movement into the main street of

town for Deepam, and her death. After the flame has consumed the ghee,

family members share the tasty mountain in tribute to Arunachala. Even

dogs get some sometimes.

At the

cattle market on the south side of the mountain, thousands of immaculate

cattle face the mountain, bells tinkling to the chewing of their cud

and the cattlemen squat together in huddles - blankets across scrawny

shoulders, by the little bonfires that contribute their own rustic

gesture of affection for this wondrous world. Light is eternal.

Very

frequently it rains at Deepam. Most of the year it doesn't rain but at

Deepam, it does. This year it is not raining and we are waiting in the

Restawhile park on the western side of the mountain; Bibidog has her

front paws crossed, she's panting. Samadhi and I have stopped refraining

from sniffing; we are suffocated with Presence. The silence deepens

towards the golden glow heralding the auspicious first appearance of the

flame. Our moon is on its way.

A soft

golden glow stirs our suspense. Then an irrepressible upsurge of human

aspiration arises, it's palpable: everyone stands up. Loving palms are

brought together above uplifted heads while millions and millions of

voices carry the stupendous sound "Ahrhoroghorah!" up to the appearance

of a tiny little flame.

Ahrhorghorah! I don't need to tell you what that means!

[Apeetha Arunagiri]

|

|

|

|